This article was originally published here by the Ethos Centre for Christianity and Society.

By now you may have read some of the analysis of the federal Coalition government’s recent budget (e.g. here, here and here), or its Commission of Audit (e.g. here, here, here or here), which was released prior to the budget in an attempt to frame our economic challenges as a ‘budget emergency’. Australia has had tough budgets before, but five factors make the 2014-15 budget a low-point in Australia’s modern history and should continue to spur Christian leaders into outspoken and courageous resistance.

First, for a government which pursued former Prime Minister Julia Gillard relentlessly on the issue of integrity for supposedly lying on the issue of a price on carbon (ignoring the fact that she came to preside over a minority government), Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s and Treasurer Joe Hockey’s wholesale trashing of so many pre-election promises is breathtakingly cynical, surprising even a jaded electorate (see here, here, here and here). Like many Australians, I have grave concerns about the ongoing corrosion of our society’s ability to develop, debate and implement sensible policy in a context where public trust is treated with contempt.

Second, as an economist I despair at the near impossibility of having a sensible public debate on economic policy in this country. Both sides of politics are to blame, but the Coalition has used its pro-business reputation as being ‘better economic managers’ to drag the ALP so far to the right as to be almost unrecognisable. The previous Labor government managed to paint itself into a corner totally unnecessarily by buying the line that an early return to surplus was the key indicator of sound economic management. Economic reality forced it into an entirely predictable and humiliating back down.

The ‘trickle down’ theory of neoliberal economics, to which both sides seem to be wedded, is intellectually bankrupt. It is based on a naive atomistic, individualistic, view of the ‘self-made man’ who does not derive his fortune in any way from public goods such as a skilled workforce funded by public education, transport infrastructure funded by public investment, an energy grid built by public utilities, a healthy population due to public health measures, or a tax-payer funded legal framework that enables markets to function. Some might praise the Coalition for at least being consistent. They don’t seem to even be pretending to have a vision for an equitable and ecologically sustainable society. The ALP meanwhile, imagines that it can aspire to such a vision mimicking the economic ideology of their opponents.

The failure to understand the legitimate role that public investment and government debt plays in running an economy illustrates the influence that neoliberal political ideology has had on policy at the expense of sound economics. Neoliberalism is obsessed with small government as a matter of principle without understanding the important role that public investment and good governance plays in sustainable prosperity. Governments can borrow at lower interest rates than private companies because they are understood by financial markets to be lower risk. Australia’s infrastructure was largely financed by public borrowing and public expenditure even before Federation: between 1860 and 1900, the share of government expenditure in domestic capital formation was around 40 per cent. Government debt was around 40 per cent of GDP for most of the period between 1910 and 1939 before spiking to 120 per cent during World War II and declining to today’s relatively low levels by the 1970s (see di Marco et al. here). Until the relatively recent fad for privatisations and public-private partnerships, most of our modern infrastructure was also built through public investment. A certain level of public debt also enables bond markets to function, providing a low-risk means for citizens to invest in the public good.

Governments should be borrowing to invest in areas where the economic return will be positive – particularly in cases such as networked infrastructure where there is a natural monopoly (meaning for example, we don’t need more than one high-speed rail route between Melbourne and Sydney, or more than one national broadband network). The Chaser team confronted Tony Abbott in 2010 with the absurdity of him saying that governments should act like households and companies in managing their debt when in fact households and companies tend to be far more indebted than the government. Australia has one of the lowest levels of public debt of any country in the OECD (see here, here and here). I was surprised to find myself agreeing with Clive Palmer recently when he said, “To say we’ve got a debt crisis means that the world’s got a debt crisis much worse than ours.”

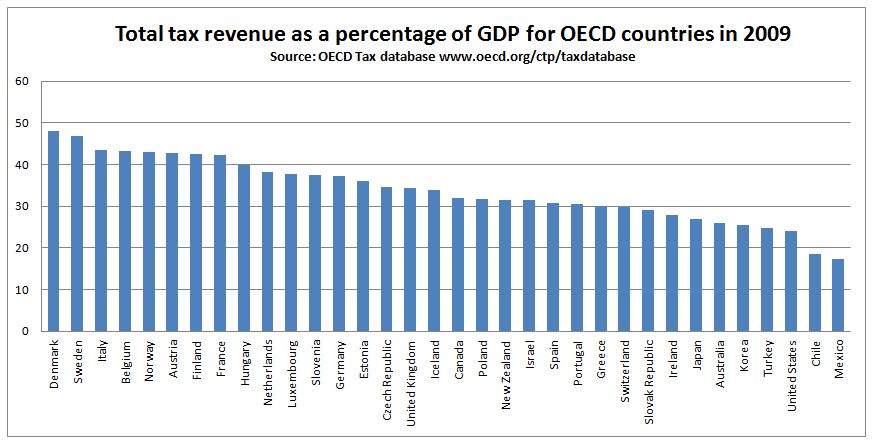

Most economists also agree that we do not have a debt crisis (see here). We do have budgetary challenges, but these are mostly on the revenue side. It is widely believed that Australia is a highly taxed country. In fact we are the fourth lowest taxed country out of the 34 countries in the OECD (yes, really). Our revenue challenges have been exacerbated by years of tax cuts in the previous decade while we rode the mining boom and rivers of gold flowed into government coffers. That was always going to slow down once the boom ended. Now we have a significant revenue problem that the federal government is seeking to palm off to the states, slashing health and education expenditure and cynically leaving the states to square the circle by raising taxes or slashing spending themselves.

Third, the government is seeking a return to surplus on the backs of the poor, the sick and the marginalised. This fact alone should galvanise Christians everywhere. Cuts of $7.5 billion to foreign aid over the four years of the forward estimates account for 20 per cent of the savings despite aid being only 1.3 per cent of the total budget (see here and here). Closer to home, the Australian Council of Social Service warned that the billions of dollars in cuts risked destroying Australia’s social safety net. Denying people under 30 income support for six months at a time and cutting benefits to poor families, is surely a recipe for increased depression and other mental health problems, family violence, alcohol abuse, suicide and crime. The $7 fee for visiting a doctor will also hit the poor – particularly those with children who suffer repeated illness and the elderly on pensions. This is likely to lead to delays in detecting serious illnesses and far more expensive treatments as a result. Raising the age of eligibility for the pension to 70 may be tolerable for sedentary office workers – but what about those doing backbreaking manual labour? Further cuts even after the budget was handed down, such as cuts to the Refugee Council of Australia have been described as “petty and vindictive”. The very real social and economic costs of all these cuts to the most vulnerable are ignored.

Fourth, the abolition of the mining tax and particularly the price on carbon pollution is a triumph of ideology and climate change denial over both economics and science. For a government that would rather cut benefits to the poor than to raise revenue from mining companies, and with no science minister, these moves were not a surprise – indeed they were election promises. If the Abbott government truly understood the threat that climate change poses to Australia but thought that the price on carbon was too high and should be lowered to serve weaker targets, that may have reflected a view that could command some respect, if not agreement. Instead the government wants not only to abolish the price on carbon, but the entire institutional infrastructure that the previous government had painstakingly established (see here and here). The Climate Commission was swiftly dispatched (and ironically, privatised, through citizen support and rebirthed as the Climate Council), and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation are under threat. A well-constructed, self-financing market-based mechanism that had begun to lower Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions significantly, is to be replaced by a ‘Direct Action’ scheme which no experts believe will work effectively and which will cost tax-payers $2.55 billion to pay big polluters to reduce their emissions if they want to (see here). This dramatic reversal has horrified foreign ambassadors, with Switzerland’s Sven-Olof Petersson saying, “I’m amazed that a Liberal government does not choose a market mechanism to regulate emissions …I think that is really shocking.” Even China is concerned, with the ABC reporting that “The Vice President of China’s most advanced carbon emissions exchange says Australia could scuttle the creation of a global carbon trading system.”

Why the intransigence? Back in 2007 in his book High and Dry, Guy Pearse, the former advisor to the Liberal Environment Minister Robert Hill, turned whistle-blower and documented how a powerful group of fossil fuel companies had essentially dictated Australia’s climate change policies. Little seems to have changed, with the Prime Minister recently declaring in his speech to the Minerals Industry Parliamentary dinner:

“Our prosperity rides on the ore and gas and coal carriers steaming the seas to our north, just as surely today as once it rode on the sheep’s back. …It’s particularly important that we do not demonise the coal industry and if there was one fundamental problem, above all else, with the carbon tax was that it said to our people, it said to the wider world, that a commodity which in many years is our biggest single export, somehow should be left in the ground and not sold. Well really and truly, I can think of few things more damaging to our future.”

Australia has enormous coal reserves and the government is working hand in glove with those who want to dig it up and export as much as possible. But once you start to take the economics of this seriously, and start to consider the wellbeing of our children and grandchildren, the case for expanding our coal exports falls to pieces (see here). Using very conservative climate models linked to even more conservative economic models, the US Government came out last year with some eye-popping figures for the so-called ‘social costs of carbon’. These models do not of course, take into account recent developments such as the fact that the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice sheet now seems unstoppable no matter what we do (see here).

What do the estimates of the social costs of carbon tell us? According to the Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (here, pp. 48 &70) Australia’s black coal exports in FY2013-14 will be around 372 million tonnes (Mt). Combustion will release around 889 Mt CO2-equivalent. For comparison, Germany’s CO2 emissions in 2011 were just 807 Mt. Based on those conservative US Government estimates, our current coal exports are causing between A$12 billion and A$110 billion of damage globally each year (in 2014 dollars). By 2018-19 the Bureau expects our coal exports to rise to 438 Mt, producing around 1045 Mt CO2-equivalent, which will cause between A$15 and A$153 billion in damage (in 2014 dollars) for expected revenues of only $49 billion. The actual profits of course would be much less. None of this damage is included in the coal export price. This is a textbook example of what economists call an externality – a social and environmental cost imposed on others by the actions of private companies. It is bad economic policy pandering to the short-term interests of powerful lobby groups.

Lastly, making higher education far less affordable by deregulating student fees is a catastrophically stupid policy. It will increase poverty levels for students, increase class-based social stratification, decrease overall skill levels in the workforce, and make public debates of complex policy issues even more difficult over time as fewer people can afford a broad education that is not narrowly tailored to a particular job. Graduates will emerge with large debts which will harm their well-being and pressure them to seek high paying jobs at the expense of more community-minded jobs such as teaching, nursing, child care, social work and public service (see here).

What are we to make of all this as Christians? I am probably not alone in feeling bewildered at what is happening to our country. So many people have been working so hard to uphold the values Jesus taught – the care for the sick and the marginalised, justice for the poor, respect and welcome for the foreigner, humility and generosity for the rich. And yet – here we are. It is inspiring to see a few church leaders and other Christians standing up, even to the point of being arrested in protest. Bravofriends! But some of the most strongly ‘Christian’ electorates voted for these cruel and regressive policies. Many of those in federal politics and their supporters who are designing and implementing these policies also call themselves Christians. Many churches continue to preach a narcissistic prosperity theology that has nothing to do with the gospel of Jesus. This surely points to a colossal failure of leadership among the Christian churches over many years – a desire to ‘play nice’, seduced by the promise of influence, and an unwillingness to consistently stand up for those Jesus placed at the centre of his concern: the poor, the marginalised, the sick, the outcast and children. Did Jesus hate rich people? Of course not. But he saw clearly that excessive wealth, selfishness and insularity were spiritual traps from which only humility, hospitality and service could free us.

If one good can come of our current malaise, perhaps it will be the re-ignition of a Christian sacred activism grounded in Jesus’ teachings, fuelled by deep prayer and with the courage to speak truth to power no matter what the cost.