This week I had the privilege of staying at Saccidananda Ashram in Tamil Nadu, India – the home of one of the greatest spiritual teachers of the twentieth century. The ashram, also known as Shantivanam (meaning ‘Forest of Peace’), lies on the banks of the Kaveri River, called the Ganges of the South. Sandy paths wind their way between red-brown huts, beneath coconut palms and banana trees. The gentle rain smells sweet.

Saccidananda Ashram was founded in 1950 as a place of meeting and interspiritual dialogue between Christians and Hindus by two French priests, Fr Jules Monchanin, who adopted the Indian name Swami Parama Arubi Ananda (bliss of the Supreme Spirit) and Fr Henri Le Saux, who adopted the name Swami Abhishiktananda (the bliss of Christ). The ashram is most famous though, for the man who arrived in 1968 and who lived there until his death on 13th May 1993, Father Bede Griffiths.

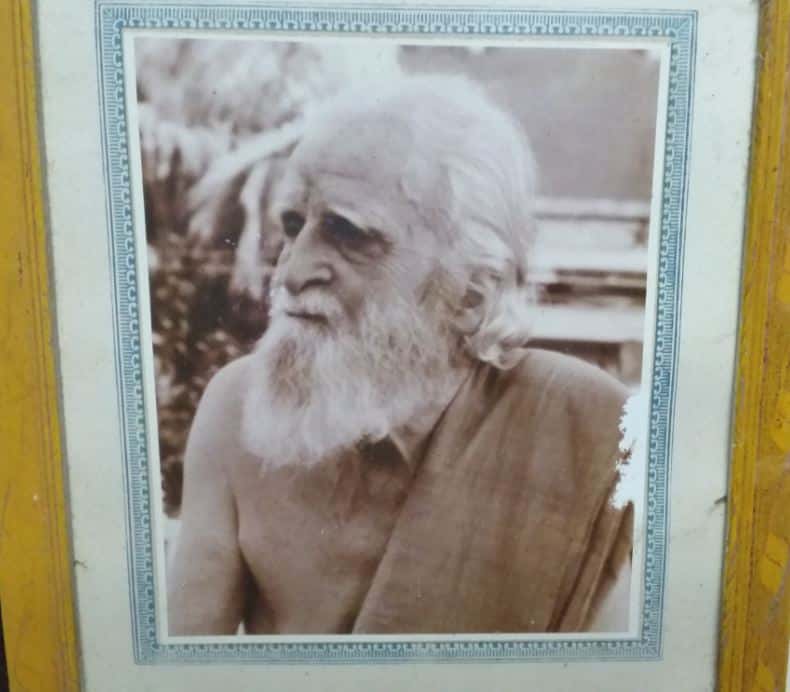

Father Bede was a towering figure of twentieth century spirituality, whose vision stretched into our own time and beyond. Born in 1906 and educated in England, he was deeply grounded in both the Christian and Indian Vedantic traditions. He was gently spoken, wrote prolifically and travelled widely, becoming a beloved figure across the word.

The Sanskrit name for the ashram, Saccidananda, means ‘Being-Consciousness-Bliss’ and was understood by its founders to be another way of describing the Christian Trinity. Bede recognised that Christianity had been largely shaped for its first 1900 years by Greek philosophical systems and Roman institutions, and that it now needed to be enriched and challenged by serious engagement with the ancient thought of India. In The Marriage of East and West (pp. 190-192) for example, he wrote:

“The doctrine of the Trinity was developed from St John’s Gospel by the Greek fathers, using the language of Greek conceptual thought, in terms of essence and nature and person and relation, and this has become the normal form of the doctrine in Christian tradition. But it is possible that the same experience could be interpreted in other terms, drawn from a different tradition. …Would it not be possible to interpret the experience of Jesus in the light of the Hindu understanding of ultimate reality? We could then speak of God as Saccidananda – Being, Consciousness, Bliss – and see in the Father, sat. Being, the absolute eternal “I am’, the ground of Being, the source of all. We could then speak of the Son, as the cit, the knowledge of the Father, the Self-consciousness of the eternal Being, the presence to itself in pure consciousness of the infinite One; Being reflecting on itself, knowing itself, expressing itself in an eternal Word. We could then speak of the Father as Nigurna Brahman, ‘Brahman without attributes’, the infinite abyss of Being beyond word and thought. The Son would then be Saguna Brahman, ‘Brahman with attributes’, as Creator, Lord, Saviour, the Self-manifestation of the unmanifest God, the personal aspect of the Godhead, the Purusha. He is that ‘Supreme Person’ (Purushottaman) of the Baghavad Gita, the ‘unborn, beginningless, great Lord of the world’, the ‘Supreme Brahman, the supreme abode, the supreme purity, the eternal divine Person (purusha), the primal God (adideva), the unborn, the omnipresent (vibhum).”

“Finally, we could speak of the spirit as the Ananda, the Bliss or joy of the Godhead, the outpouring of the super-abundant being and consciousness of the eternal, the Love which unites Father and Son in the non-dual Being of the Spirit. This Spirit is also the Atman, the Breath (pneuma) of God, which is in all creation and gives life to every living thing, which in humanity becomes conscious and grows with the growth of consciousness until it becomes pure, intuitive wisdom. The Atman is the Spirit of God in humanity, when the human spirit becomes pervaded by the divine spirit and attains to pure consciousness. It is conscious Bliss, consciousness filled with joy, with the delight of Being. This was the spirit that filled the soul of Jesus and gave him perfect consciousness of his relationship as Son to the perfect ground of Being in the Godhead.”

“Hindu experience can also help bring out another aspect of the godhead, the concept of God as Mother. The Hebrew tradition was patriarchal, and Christianity has preserved only a masculine concept of God. The Father and the Son are masculine in their very names, and even the Spirit, which is neuter in Greek, has been given a masculine character. But the Hebrew tradition also preserves a word for the spirit (ruah) which is feminine, and in the Syrian church this feminine gender was preserved so that they could speak of the Holy Spirit as Mother. There is also in the Old Testament the beautiful figure of Wisdom (hocmah) which is also feminine. …”

“But it is in the Holy Spirit that the feminine aspect of the godhead can be most clearly seen. She is the Sakti, the power, immanent in all creation, the receptive power of the Godhead.”

It was both humbling and deeply moving to pray and meditate in Bede’s small hut, with its wicker bed, simple wooden chair and modest book case. In that small place I had the sense of being connected to a vast, spacious, blissful ocean of peace. Not a sleepy, placid peace – rather a peace crackling with Divine energy and power – the Shakti of God. I could have swum in that ocean forever.

The ashram’s work continues under the leadership of Brother Martin, a prolific author and speaker in his own right. Though it is primarily a place for prayer and meditation, the ashram also runs a number of social programs to help the poor. It operates a home for the aged and destitute, provides books, clothing and school uniforms for some 420 local children each year, and also provides milk to children under three years of age to supplement their nutrition.

What a joy to have the chance to stay in a place, not only of tremendous historical significance, but also one which continues to nurture deep interspiritual transformation and which provides an ongoing example of true sacred activism.